Welcome to Part #2 of my look at how Irish identity has been explored, constructed and presented through design and exhibitions. This part looks at some key exhibitions and presentations in the 19th and 20th centuries, contrasting the different ways that design and manufactures were presented at home and abroad, and exploring the struggle between presenting tradition and rurality and presenting progress and modernity. Read back on Part #1, while Part #3, looking at Irish design exhibitions now and next, will be posted next week, so stay tuned!

Irish Exhibitions of the 19th Century

It was as early as 1834 when the Royal Dublin Society decided to organise an exhibition of Irish manufactures in the Dublin Drawing School. The enthusiasm of the Society led to another exhibition in 1835, but after that, space and organisational issues led to the Society's exhibition becoming triennial. The RDS Exhibitions would occur every three years, showing fine art and manufactures from all over the country to a national audience in various venues in Dublin. Ireland would participate in international exhibitions beginning with Britain's Great Exhibition of 1851 and began hosting international exhibitions of its own, both in Dublin and Cork in the years 1853, 1865, 1902 and 1907. Ireland's national and international exhibitions had similar aspirations as the exhibitions in other nations during the period. The promotion and improvement of manufactures was key, as was a nationalist or patriotic spirit. In addition to promoting Irish industry within Ireland, these exhibitions were intended to show Irish industry to be of a standard in line with foreign competition.

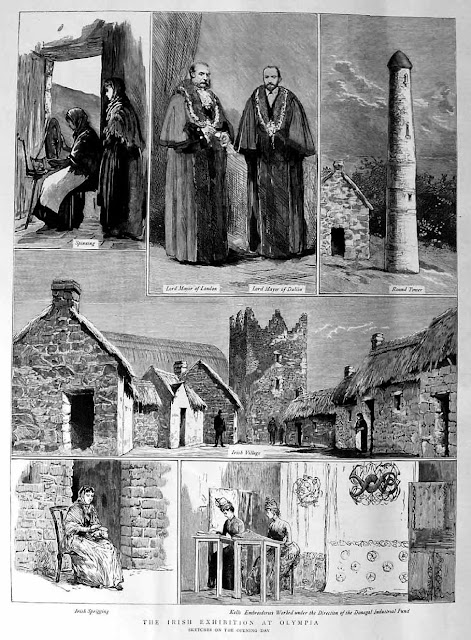

But interestingly, where the exhibitions held within Ireland would place great importance on industrial prowess and technical innovation, in terms of the exhibits on show and the venues chosen or created, Ireland's participation in exhibitions abroad gradually took on quite a different look and feel. Where Ireland was presented to an Irish audience as being an industrial nation on par with its neighbours, when presented to a foreign audience, from the Irish Exhibition in London's Olympia in 1888 onwards, Ireland was presented as being a decidedly rural nation, whose output was predominantly craft-based. The Olympia exhibition (illustrations of which are pictured above) was the first time that the exhibition 'pavilions' consisted of thatched cottages and replicas of Irish castles and monuments. The exhibition even contained a 'working' farmyard complete with livestock, reinforcing the image of a nation who relied above all else on agriculture. Experience was prioritised alongside environment, with the space populated by 'peasants' who would demonstrate traditional textile techniques such as dyeing, carding, spinning, and weaving by hand. Such an exhibition was totally at odds with the exhibitions held within Ireland, but became the norm for Ireland's presentations abroad. This presentation of a rural nation continued at international exhibitions, notably at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where not solely presentation but performance of Irish rurality was key. Demonstrations in craft techniques relating to textile production, Connemara marble and bog oak carving were accompanied by harp playing, singing, dancing and oration of Irish verse.

Irish Exhibitions of the 20th Century

In the international exhibitions of the early 20th century, Ireland's presentations continued along the same vein, creating villages of cottages, replica round towers and versions of famous castles, populated by peasant craftworkers and featuring performances, demonstrations and other 'entertainments'. This style of presentation appears to become increasingly commercial and cynical, a key example of this being 'Ballymaclinton', a village of thatched cottages presented by McClinton's Soap Company at no fewer than four international exhibitions. As the 20th century progressed, Ireland began to embrace modernity and internationalism, and the participations spearheaded by the Free State government took on a different tone... to an extent. The Empire Exhibition in Glasgow in 1938 was the first such presentation taken on by the Free State government and it was intended that Ireland's pavilion would combine Irish materials with a modern design 'to echo the modernity of the rest of the exhibition' (as quoted by Deirdre Campion). The following year would see a triumph of Irish modernism in the form of architect Michael Scott's pavilion for the New York World's Fair (pictured above), though even when faced with the sleek white modernist shell created by Scott, the rural image nevertheless had its part to play.

Commissioned to create a pavilion of ‘strong and recognisable Irish character’, as Scott said in an interview with Nicholas Sheaff, Scott designed a two-storey building in the shape of a shamrock; within each leaf was housed a gallery for a different Irish industry and in the stem was a mural gallery featuring work by Irish artists Sean Keating and Maurice McGonigle and – naturally – a tourist information space. A central spiral walkway and continuous ramping routes brought the visitor round a building employing a minimum of decoration, with space on the facade reserved for a sculpture of a young woman by Frederick Herkner (inspired by a line of poetry by W.B. Yeats, ‘your mother Éire is always young’) and typesetting by Eric Gill. A sleek and accomplished pavilion, it was selected by an international jury as the best building in show and earned Scott honorary citizenship of the city of New York.

In stark contrast to this modernist representation of an emergent nation however, Ireland was also represented in the fair's amusement section. 'A Trip Thru Ould Ireland' consisted of replicas of a number of famous Irish sites, including the Giant's Causeway, Dunluce Castle and Blarney Castle. While the striking modernity of Scott's pavilion clearly impressed many, there was no doubt in the organisers' minds as to the drawing power of a quaint old Irish village selling souvenirs from the Emerald Isle. As writer Deirdre Campion notes, 'the contrast between the two exhibits could not be greater and shows very clearly the problems Ireland itself was having in building a new image, with so much emphasis on the old and the pastoral conflicting with its entry into the modern world'.

Ireland's most notable international presentations following the New York World's Fair of 1939 came in the form not of exhibitions per se but in presentations at numerous trade shows and a number of in-store installations in American department stores in the 1960s and 1970s. It should be noted that a major multidisciplinary arts presentation occurred in London in 1980 in the form of A Sense of Ireland, a six week festival of theatre, literature, music and more, designed to 'saturate' the UK capital but craft featured only to a small extent, and design not at all. Rather, it is trade shows and in-store promotions where Ireland's design was most notably shown, and two such installations are written about in depth by Anna Moran in Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992: a five year-long display at B. Altman Fifth Avenue in New York from 1967-72 and an Irish Fortnight in Neiman-Marcus, Dallas in 1976 were devised specifically to promote and sell products, many made in Kilkenny Design Workshops (KDW), and are examples once again of the fine balancing act between an image of rurality and an image of modernity that Irish presentations have found themselves engaging in. Once again design and craft are entwined, and once again a rural environment is created and rurality is performed through demonstrations by real life Irish people. For all the strives being made in KDW to modernise, employ technology and use contemporary aesthetics, its output is framed by the rural.

Read back on Part #1 of this series and stay tuned for Part #3, coming to I Like Local soon. Great further reading on Irish design includes Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992 edited by Linda King and Elaine Sisson and Kilkenny Design: 21 Years of Design in Ireland by Jeremy Addis and Nick Marchant. Deirdre Campion's thesis, Manifestations of a Nation, Ireland: Exhibitions and Symbols 1850-1950, is available to read in the the V&A's National Art Library.

Images via 1 | 2&3

Irish Exhibitions of the 19th Century

It was as early as 1834 when the Royal Dublin Society decided to organise an exhibition of Irish manufactures in the Dublin Drawing School. The enthusiasm of the Society led to another exhibition in 1835, but after that, space and organisational issues led to the Society's exhibition becoming triennial. The RDS Exhibitions would occur every three years, showing fine art and manufactures from all over the country to a national audience in various venues in Dublin. Ireland would participate in international exhibitions beginning with Britain's Great Exhibition of 1851 and began hosting international exhibitions of its own, both in Dublin and Cork in the years 1853, 1865, 1902 and 1907. Ireland's national and international exhibitions had similar aspirations as the exhibitions in other nations during the period. The promotion and improvement of manufactures was key, as was a nationalist or patriotic spirit. In addition to promoting Irish industry within Ireland, these exhibitions were intended to show Irish industry to be of a standard in line with foreign competition.

But interestingly, where the exhibitions held within Ireland would place great importance on industrial prowess and technical innovation, in terms of the exhibits on show and the venues chosen or created, Ireland's participation in exhibitions abroad gradually took on quite a different look and feel. Where Ireland was presented to an Irish audience as being an industrial nation on par with its neighbours, when presented to a foreign audience, from the Irish Exhibition in London's Olympia in 1888 onwards, Ireland was presented as being a decidedly rural nation, whose output was predominantly craft-based. The Olympia exhibition (illustrations of which are pictured above) was the first time that the exhibition 'pavilions' consisted of thatched cottages and replicas of Irish castles and monuments. The exhibition even contained a 'working' farmyard complete with livestock, reinforcing the image of a nation who relied above all else on agriculture. Experience was prioritised alongside environment, with the space populated by 'peasants' who would demonstrate traditional textile techniques such as dyeing, carding, spinning, and weaving by hand. Such an exhibition was totally at odds with the exhibitions held within Ireland, but became the norm for Ireland's presentations abroad. This presentation of a rural nation continued at international exhibitions, notably at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where not solely presentation but performance of Irish rurality was key. Demonstrations in craft techniques relating to textile production, Connemara marble and bog oak carving were accompanied by harp playing, singing, dancing and oration of Irish verse.

Irish Exhibitions of the 20th Century

In the international exhibitions of the early 20th century, Ireland's presentations continued along the same vein, creating villages of cottages, replica round towers and versions of famous castles, populated by peasant craftworkers and featuring performances, demonstrations and other 'entertainments'. This style of presentation appears to become increasingly commercial and cynical, a key example of this being 'Ballymaclinton', a village of thatched cottages presented by McClinton's Soap Company at no fewer than four international exhibitions. As the 20th century progressed, Ireland began to embrace modernity and internationalism, and the participations spearheaded by the Free State government took on a different tone... to an extent. The Empire Exhibition in Glasgow in 1938 was the first such presentation taken on by the Free State government and it was intended that Ireland's pavilion would combine Irish materials with a modern design 'to echo the modernity of the rest of the exhibition' (as quoted by Deirdre Campion). The following year would see a triumph of Irish modernism in the form of architect Michael Scott's pavilion for the New York World's Fair (pictured above), though even when faced with the sleek white modernist shell created by Scott, the rural image nevertheless had its part to play.

Commissioned to create a pavilion of ‘strong and recognisable Irish character’, as Scott said in an interview with Nicholas Sheaff, Scott designed a two-storey building in the shape of a shamrock; within each leaf was housed a gallery for a different Irish industry and in the stem was a mural gallery featuring work by Irish artists Sean Keating and Maurice McGonigle and – naturally – a tourist information space. A central spiral walkway and continuous ramping routes brought the visitor round a building employing a minimum of decoration, with space on the facade reserved for a sculpture of a young woman by Frederick Herkner (inspired by a line of poetry by W.B. Yeats, ‘your mother Éire is always young’) and typesetting by Eric Gill. A sleek and accomplished pavilion, it was selected by an international jury as the best building in show and earned Scott honorary citizenship of the city of New York.

In stark contrast to this modernist representation of an emergent nation however, Ireland was also represented in the fair's amusement section. 'A Trip Thru Ould Ireland' consisted of replicas of a number of famous Irish sites, including the Giant's Causeway, Dunluce Castle and Blarney Castle. While the striking modernity of Scott's pavilion clearly impressed many, there was no doubt in the organisers' minds as to the drawing power of a quaint old Irish village selling souvenirs from the Emerald Isle. As writer Deirdre Campion notes, 'the contrast between the two exhibits could not be greater and shows very clearly the problems Ireland itself was having in building a new image, with so much emphasis on the old and the pastoral conflicting with its entry into the modern world'.

Ireland's most notable international presentations following the New York World's Fair of 1939 came in the form not of exhibitions per se but in presentations at numerous trade shows and a number of in-store installations in American department stores in the 1960s and 1970s. It should be noted that a major multidisciplinary arts presentation occurred in London in 1980 in the form of A Sense of Ireland, a six week festival of theatre, literature, music and more, designed to 'saturate' the UK capital but craft featured only to a small extent, and design not at all. Rather, it is trade shows and in-store promotions where Ireland's design was most notably shown, and two such installations are written about in depth by Anna Moran in Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992: a five year-long display at B. Altman Fifth Avenue in New York from 1967-72 and an Irish Fortnight in Neiman-Marcus, Dallas in 1976 were devised specifically to promote and sell products, many made in Kilkenny Design Workshops (KDW), and are examples once again of the fine balancing act between an image of rurality and an image of modernity that Irish presentations have found themselves engaging in. Once again design and craft are entwined, and once again a rural environment is created and rurality is performed through demonstrations by real life Irish people. For all the strives being made in KDW to modernise, employ technology and use contemporary aesthetics, its output is framed by the rural.

Read back on Part #1 of this series and stay tuned for Part #3, coming to I Like Local soon. Great further reading on Irish design includes Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992 edited by Linda King and Elaine Sisson and Kilkenny Design: 21 Years of Design in Ireland by Jeremy Addis and Nick Marchant. Deirdre Campion's thesis, Manifestations of a Nation, Ireland: Exhibitions and Symbols 1850-1950, is available to read in the the V&A's National Art Library.

Images via 1 | 2&3